We did so much this week. It’s actually incredible how much you can fit into a 40 hour work week.

I ended last week’s by talking about our okapi feeder enrichment project for the Houston Zoo. As of the end of Thursday, we finished brainstorming and we spent all of Friday working through Pugh Screening and Pugh Scoring matrices to select our final design. It was a good process to go through, but it’s also an extremely boring and exhausting one, so I will spare you from the gory details and just tell you that the okapi-powered fidget spinner was not selected as our final design.

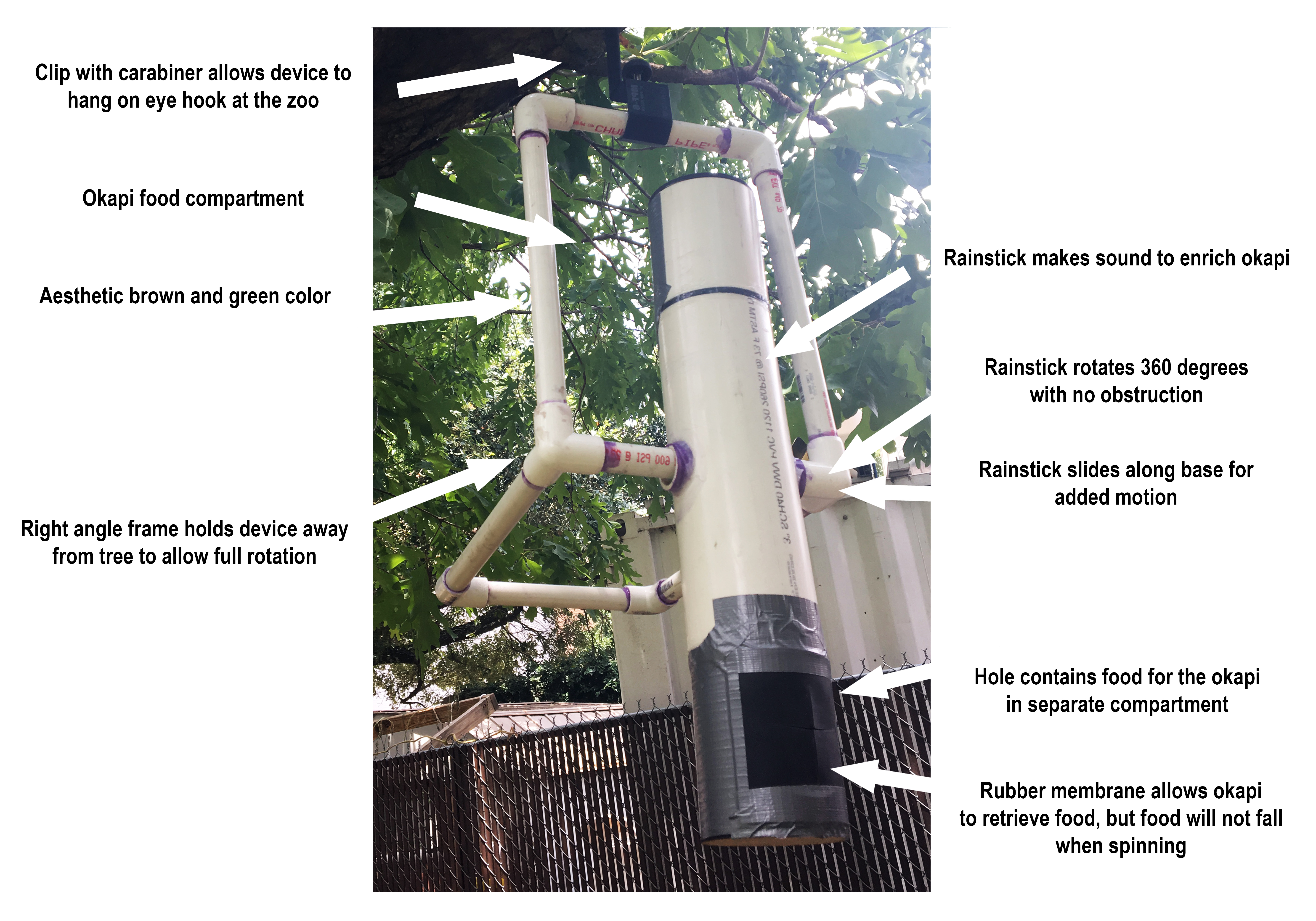

Instead, we created a spinning rainstick okapi feeder to enrich them through the use of movement, sound, and food. It functions as a PVC pipe along an axle with a rainstick in the middle and food compartments on each end. That way, the okapi can spin the feeder to hear the sound of the rainstick and get to the food stored in various locations on the rainstick.

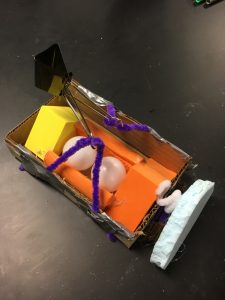

After we selected our final design on Friday, the next thing to do was jump straight into prototyping on Monday. However, because this was boot camp, it was also important to review / relearn about the prototyping process as opposed to just jumping into sawing PVCs to make our prototype. And so, Dr. Wettergreen issued us a challenge. When he visited Addis Ababa a couple of years ago, he rode in a bajaj, which is a type of taxi that is super unsafe. There are no seatbelts, no airbags, and no safety features. So Dr. Wettergreen gave us half an hour to use low-fidelity materials (like straws, cardboard, foam, pipe cleaners, etc.) to build a newer, better bajaj. The rules were that we had half an hour to build a bajaj that wouldtake a driver and a passenger safely from one end of the path to the other. We couldn’t cage the passengers in (because real bajajes do not have seatbelts) but they had to survive the journey without falling out of the cart. We were split into teams of two to build them, and Carlos and I worked together to build an incredible bajaj that had foam airbags, a cardboard carrier, and bumper on the front made of pipe cleaners and foam.

The next logical thing is to race the bajajes down the OEDK zip line to determine which was truly the blue-ribbon bajaj. It was super cool to see everyone’s radically different designs. Ours was more traditional, but there was one that looked like a canoe, one that had spikes along the top of it, one with flames coming out of the back of it, and one with a spring made of cardboard. So we each launched our bajajes down the zip line spanning from the first floor to the basement. Ours did really well with a time of 5.00 seconds to the bottom, and we were in first place until Jeremy the TA’s cardboard-spring loaded bajaj flew down the zipline at 4.13 seconds. Which, Wow.

I’d like to think we took our defeat with grace.

So, we spent the rest of Monday morning working with low-fidelity materials like straws, construction paper, tape, cardboard, etc. to flesh out our ideas and plans for building the actual prototype that afternoon. The logic for using low-fidelity materials is that they are easier to work with, so skill level isn’t really a factor in being able to solve problems. Anyone can glue cardboard together, so working with low-fidelity prototypes to solve challenges is much more of a test of creativity than that of being a skilled engineer. Low-Fidelity materials are also great for working through design challenges on one’s prototype with materials that are faster and much easier to work with, so if I were to mess up building a low-fidelity prototype because my design was unsound, it’s a lot faster to fix it.

Once we worked through the logistics of our design on the low-fidelity prototype, we spent Monday and Tuesday speed-building our device out of medium-fidelity materials, such as PVC and wood. Even though we worked through the logistics of the design itself when building the low-fidelity prototypes, we still had to overcome all of the challenges of using medium-fidelity materials to build our device. I had personally never worked with PVC before, so that was a learning experience. I laser cut acrylic disks to separate the rainstick portion of our device from the food containers until we realized that we couldn’t actually glue acrylic and PVC together, so we had to use wood. We tried to saw a 3-inch PVC pipe down to size only to realize that hand saws and chop saws and even vertical mills are fairly inaccurate when it comes to PVCs, so we had to sand the PVC pipes down to make them even enough to glue together. We learned how to use a hole saw to create the openings for the okapi to access the food and… actually, I don’t think there were any problems with that. But after the trials and tribulations that come from any prototyping session (especially a prototyping session squeezed into two days), we did emerge on Tuesday afternoon with a working prototype that we could present to both our professors and the zoo.

And with our final presentation to our professors, we were finished with boot camp. We went through the entire engineering design process in five days. It was insane. It was exhausting. But it also… was kind of exhilarating? There’s something about only having a limited amount of time to speed-build something and have it come out the other end actually being able to function that provides an adrenaline rush and also strong a feeling of pride. This is one of the reasons why I chose engineering: I like being able to build something that will work to affect the world around me.

We also participated in a Needs Finding Workshop, in which we talked about problems that affected us and should be solved, wither through engineering or other means. For instance, Kelvin complained about a sidewalk on campus that was frustrating to walk on because there are like 4-inch gaps between the tiles, and it’s difficult to bike or walk on because of the various textures and heights of the tiles. Even though this might not seem like a big deal, we learned that it actually is a problem because people can easily trip and hurt themselves on this sidewalk. We also learned about empathy by simulating disabilities so we can see what challenges are faced by those with disabilities. For instance, we learned that trying to eat with arthrogryposis is extremely difficult when you can’t really move your arms, it’s extremely hard to open keyswipe doors when you’re blind, and that trying to roll a wheelchair up a ramp is insanely difficult.

|

|

|

| Simulating blindness with my jacket and a yardstick | Attempting to eat cereal while simulating arthrogryposis | Riding around in a wheelchair is hard work! |

We finished boot camp on Tuesday, so on Wednesday we got our actual projects for the summer (no rest for the weary, am I right?). I am proud to announce that Liz, Alex, Blessings, and I will be working to improve a casting stand for people to lean on when they are casted for prosthetic legs. Because the patient often does not have the strength to hold themselves up and because the casting process takes a long time, they need to lean on something while the cast is hardening. The current solutions for this problem are to make the patient support themselves on parallel bars or t put them in a harness; both of these solutions are expensive and uncomfortable. So we are making a better solution.

A previous team already started this project first semester, and although they did technically reach a finished product whose functions all work, it is definitely not ready for actual users. Although it looks very nice at first glance, upon closer inspection, the current prototype is actually not very high quality. It’s extremely rickety, a lot of the weight is supported on a single pin, it’s difficult to adjust, and it’s not very comfortable.

We are currently conducting research about the best ways to improve this casting stand. Current ideas include making the height adjustable like a drill press or a bike seat. We are considering adding straps for the chest and drawer slides bigger cushions. We will meet with the client today to do more research, and then we will get to work on deciding and learning how exactly we are going to improve this device. It’s likely that I am going to have to learn a lot of advanced machining techniques to fix this, such as welding and using lathes and vertical mills and SolidWorks. So, that’s kind of terrifying, but I’m excited about seeing what we will do by the end of the summer.