What a week! Can’t Brachius has gone from having a couple chosen solution ideas for our project to producing a fully functional prototype of both the contracted shoulder with selectively limited motion and the “normal” shoulder that can perform all the exercises needed!

Friday I think everyone in our team walked away with some new skills. We broke out the magical website that is MakeABox and popped out an Illustrator file for laser cutting a finger joint box in the exact dimensions we needed. Oops, it uses interior dimensions so subtract half an inch from each side to account for the thickness of our 1/4″ birch plywood- there, now the size we need. Grant showed the team how to use epoxy as we set up a test for the magnet capsule, attaching disk magnets to dowels. We all got a taste of Adobe Illustrator in the afternoon’s workshop, and put it to use making a scapula file. We went to the laser cutter, and used that wonderful machine to create the trunk box, scapula and a device called a slip disk to allow smooth rotation for our scapula-trunk connection. We also found some Thingiverse files and Liz showed us how to use a couple 3D printers to make some humerus bones and a hinge. It turns out that scaling down an adult humerus to 30% size looks uncannily fragile, (human bones don’t start that skinny) so we adjusted the scale on the X and Y axes to make the bone thicker.

Finally, we learned how brittle magnets can be. Our neodymium sphere and countersunk ring magnets arrived. We played with them and wow, 14 lb of pull in a 3/4″ diameter sphere is impressive! Less impressive is the fact that when I let the ring magnet jump to meet it, that couple of inches in the air gave it enough force to give off a spark and snap the poor thing in half. Okay fine, that’s also impressive, just saddening.

On Monday, Can’t Brachius was in a rut while waiting for our goosenecks, more magnets and other materials to arrive. Grant and Rebeca were researching wood stains and lacquers. Xiaoyao and I were slowly learning about Illustrator while trying to modify the MakeABox outlines from 3 boxes and combine them into one “Utah box” with an inset for the scapula. Useful things to know, but not exactly pressing matters. We’d tried mocking up a magnetic ball and socket and the epoxy did not hold the magnets long enough to fully see their capabilities.

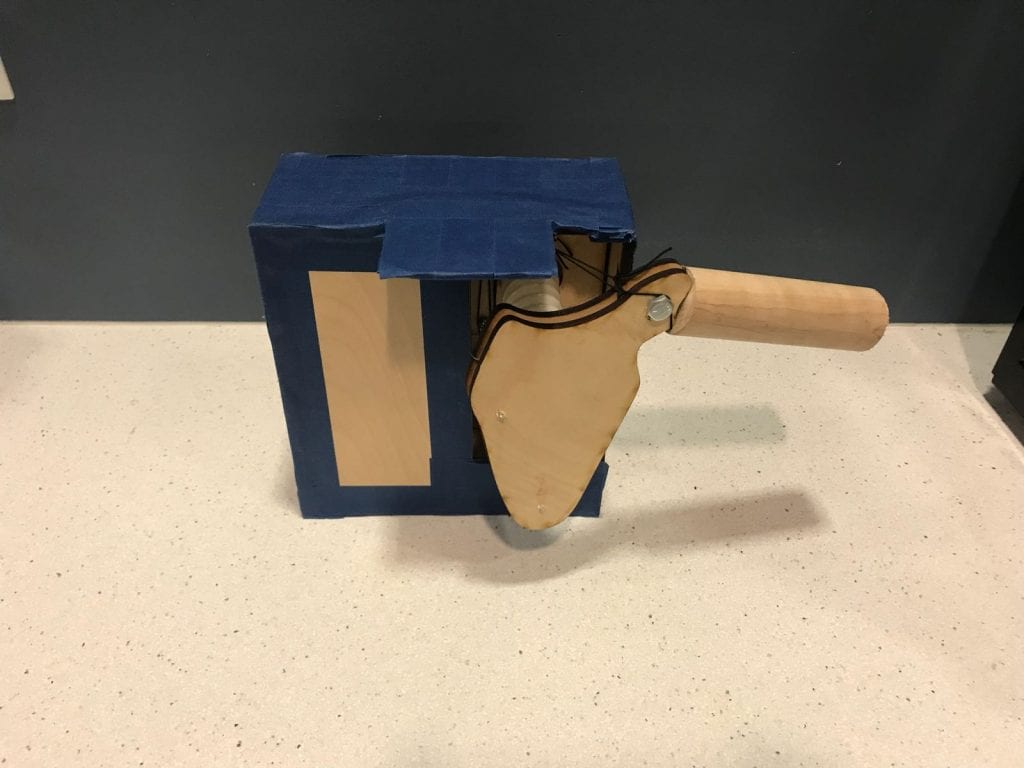

Then around 1 pm, Dr. Wettergreen, just returned from Malawi, met with us and he and Dr.Hunter talked through our project’s status. They advised against using 3D printed bones (too eery) and directed us toward using dowels and other materials available at the OEDK rather than staying dependent on magnets that had not proven durable. Dr.Wettergreen suggested we build a prototype at large scale (no tiny scapula) and present it at the next day’s morning meeting. Uh… alright then. And we’re off! We went into a frenzy of laser cutting, drilling, and minute-to-minute problem solving. What elastic can hold the shoulder joint together? Ooh, here’s some stretchy tubing! How do we attach tubing to a flat plywood disk? Paperclips can make metal wire! We finished throwing together our first prototype in under 4 hours, albeit attaching some parts with duct tape.

Tuesday morning I drove to work for the first time ever! I’m working on getting my license by the end of the summer. Needless to say, I was full of adrenaline when I got to the OEDK, and I pretty much stayed that way for the whole day. In the morning meeting we presented our brand new prototype, and tried the movements for the first time showed the exercises it could perform. We stayed after the morning meeting and Drs. Hunter and Wettergreen went through a thorough critique of our prototype. They had us take them through some exercises and contractors and quizzed us on whether it was performing the motions as needed. I, um, had specific ideas of what were real flaws of the design versus aspects not within the scope of our project as James defined it and I *cough cough* had trouble not piping up with a rebuttal to every point they made (see: full of adrenaline). I’m working on the taking advice and criticism side of things.

Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday we really got into the iterative process of prototyping. First we differentiated the shoulder prototypes and built the two models to demonstrate the contractures and exercises separately. As we went, we worked on the connection points between different elements and gradually increased the strength and fidelity of our mechanisms. Put a chain link in to fuse the contracted shoulder. Try a torsion spring to un-fuse the shoulder but restrict movement. Change the paperclips to copper wire. Add elastic to hold the scapula more parallel to the trunk. Add dowels to restrict motion. After lots of trial and thankfully not too much error, we had a functioning prototype for each side of the model and a trunk assembled that could hold a combined model. Once we added larger base boxes to each model, they looked much more proportional and complete, and could lie on their ‘backs’ as intended.

At this point, we had many questions about how to move forward. The scale was still double the size of a newborn, and our mechanisms were mainly working but we had been struggling to make the scapula rest closer to the surface of the trunk. We weren’t clear on how exactly it should be better. It was time to schedule a meeting and get some more information. Luckily, our wonderful client, James, turned out to be free the next day! We packed our models into a box and took it to lunch with us on our way to the BRC in the Medical Center afterwards. As Xiaoyao put it,

“In this box we have 3 half babies.”

-Xiaoyao

The meeting was a success! James devoted 2 hours to discussing our progress, seeing the ins and outs of our models, telling us how each part measured against his ideal dimensions, and so much more. To our surprise, he likes demonstrating with the model scapulas facing upwards! He and we alike had assumed the model should be parallel to the anatomy of a baby lying on its back, but as he was trying it out he found that he could show many movements clearly with the model flipped over as if there were X-ray vision seeing through the baby. Who’d have guessed? And here we were trying to get the scapula closer to the trunk and more anatomically correct!

It’s great to talk to James and see what we need to focus on moving forward, what the priorities are and what changes should be made. Our focus going forward will now target improving durability while maintaining function, increasing the range of the contracted motion in horizontal adduction, and eliminating the need for external visible supports (such as elastic) on the scapula.

Now we know!