This has been a super busy week for Team Gotta Cast ‘Em All! As the materials we ordered on Friday started arriving, we were able to work on putting together our prototype. Because most of the materials we wanted to work with aren’t kept in regular stock at the OEDK (long metal struts, foam, vinyl, grip tape, dolly wheels, etc), we had been kind of at a prototyping standstill until our parts started arriving on Monday. Unfortunately, a lot of those parts we needed for finishing the device (wood screws, grip tape, etc) were the parts we needed to finish the device, and the parts we needed to build the structure of the device (metal tubing, foam for cushions, etc) wasn’t arriving, so that was a major point of stress for our team this week.

Fortunately, enough of our parts did arrive in a [relatively] timely manner, and between using what we did receive and the supplies we found around the OEDK, we were able to get a lot done with the resources and time we had. While Liz and I had been working on sewing the cushions together (or rather, Liz was sewing while I did some of the prep work), Alex and Blessings finished creating the CAD model last week, so using that as our guide, we were able to start machining the parts we would need. Jeremy took us into the machine shop where he taught us how to use practically every machine to build the pieces necessary for our prototype.

The final CAD model for the Hybrid Casting Stand. We used this extensively for putting our prototype together this week.

I have been working with wood for most of my life, so I’m fairly comfortable putting things together using a hammer and nails. My engineering design project last year was made almost entirely out of wood, so I learned how to use hand tools like jigsaws and dremels through that. But metal is a completely different ball game. It is so much more complicated (and dangerous) to cut, sand, and put together because most metal-working involves superheating it for it to do anything.

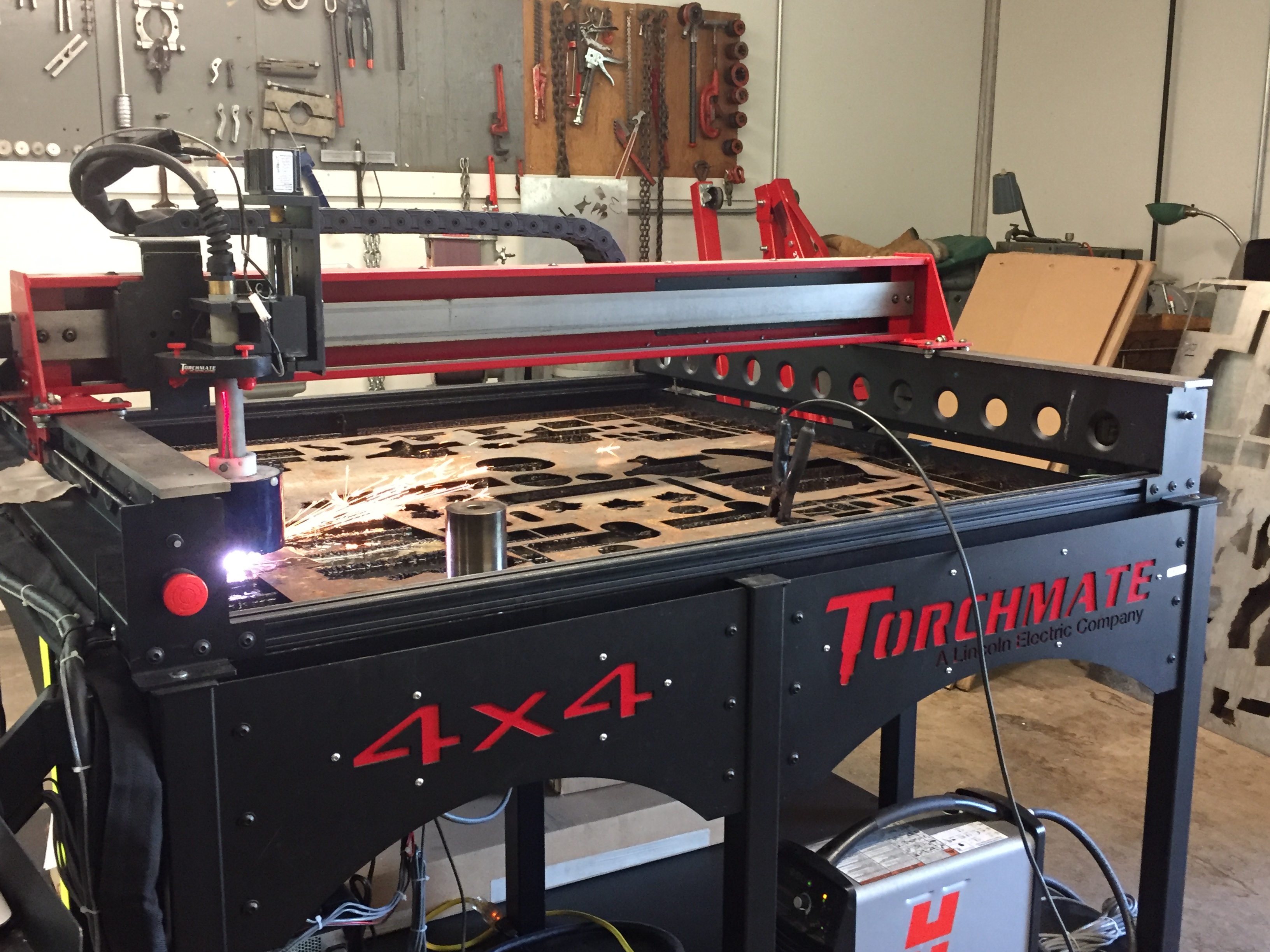

We had a large number of complicated connections in our design, so we needed a large number of custom brackets so we could create things like a handle to move our device vertically, brackets to secure the arm cushions to the armrests, and connections to hold two bars to the back cushion while allowing tubing to slide around them. Because we needed to cut sheet metal to create these brackets, Jeremy taught us how to use the plasma cutter, which is essentially the laser cutter’s bigger, badder, brutish older cousin. Similar to how the laser cutter uses a laser to precisely cut wood, the plasma cutter essentially superheats the metal into plasma to cut shapes out of it, which results in some dangerous electrical current and an awful lot of sparks. Although the plasma cutter isn’t nearly as precise as the laser cutter, you can use it to cut some fairly complex shapes, like maple leaves, the OEDK logo, and the state of Texas (if you look closely, you can see those shapes in the metal we used to cut our brackets).

I remember learning about the states of matter in 3rd grade science class, and my teacher talked about plasma, the 4th state of matter that I had never heard of before. I was really confused so I asked for an example of plasma in real life, and she told me that plasma doesn’t exist on Earth. Evidently, she was wrong because I’m sitting here today harnessing the power of plasma to cut pieces for our humble little engineering project.

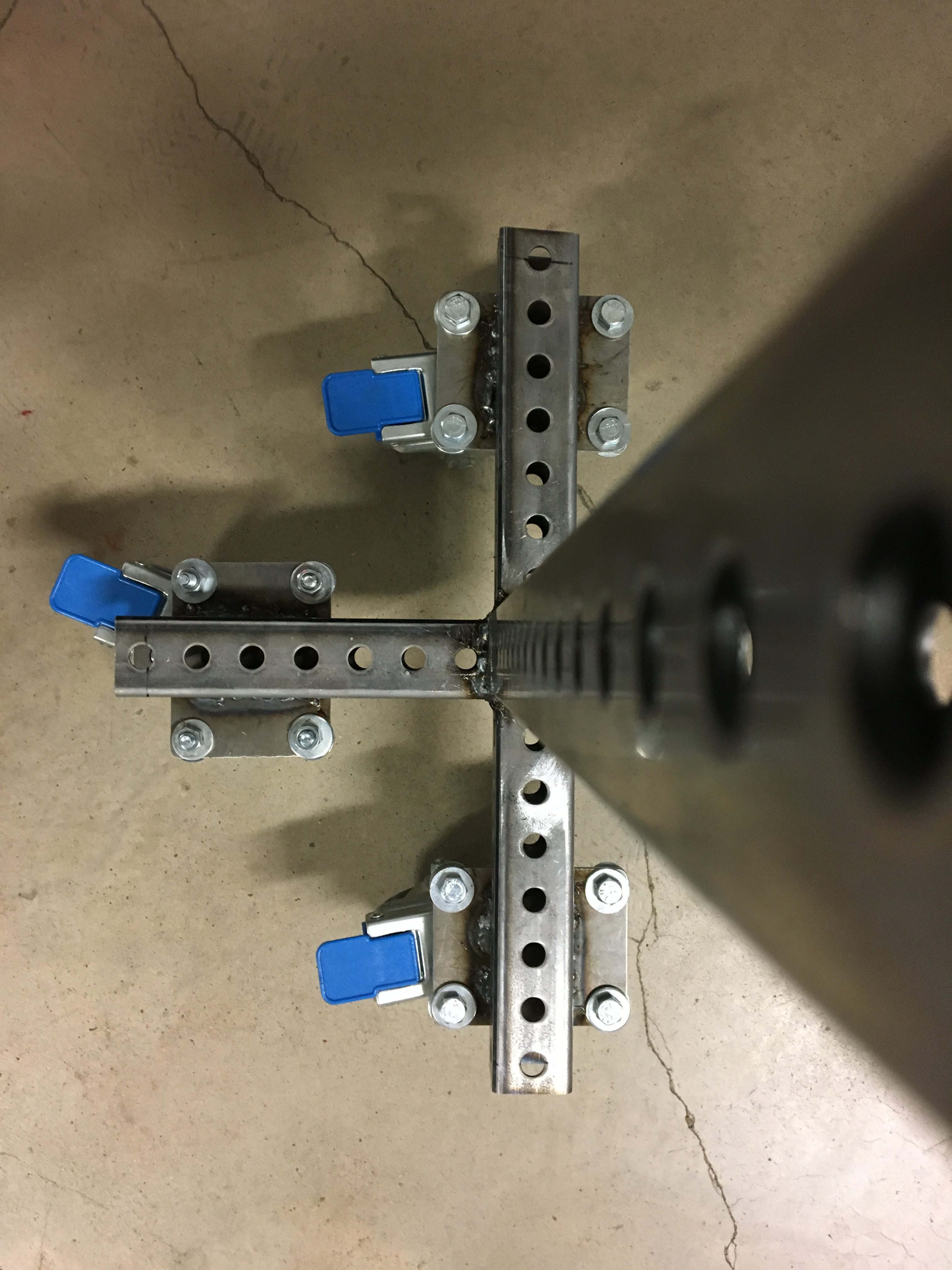

While I was using the plasma cutter, Jeremy was machining a piece for us to connect the legs of our device to the dolly wheels we planned to use for the front legs of our device. We decided to use dolly wheels because they provided a platform for the legs to remain upright, but the only point of connection they offered was through a hole that allowed a bolt to up up into the hollow struts we were using as legs. So it was necessary to create a connecting piece for them, and that’s where Jeremy’s extensive knowledge of the machine shop came in handy. From the drawings Alex made in SolidWorks, Jeremy was able to use the lathe and the CNC to build our piece. Blessings and I used the vertical mill to drill out the holes for the bolts that actually connect the wheels with the legs, and then we used a tap to thread the hole we had drilled. It was really cool how we were able to create something custom-fit to our needs from what was once a solid hunk of aluminum.

As our metal struts came in, we began measuring and cutting them down so we would have our parts ready to weld for our design. Joe, the master of the machine shop and the welding lab, was missing, so we could’t get access to the Johnson Saw, which would have been the best way to cut our metal struts. So instead we just pulled out the chopsaw in the machine shop to cut our metal struts down to size. It was a little less precise and a little more dangerous, but we got the job done and at the end of the day, Jeremy says that was the more fun option of the two, so I guess it all worked out in the end.

Alex looking powerful while using the chopsaw. That was me for about three cuts, but then I accidentally burned myself on some recently cut metal and proceeded to spend the rest of the afternoon nursing my would with a pickle-flavored ice pop I found in the OEDK freezer.

Although the primary focus of this internship is to design engineering solutions for global health problems, a large part of this internship involves learning about other cultures from our international counterparts, but this also works in reverse. So on Wednesday, all of the OEDK interns took a field trip to the Astros game at Minute Maid park (which apparently used to be called Enron Park until, well, you know) to teach the international students about American baseball. We sat like three rows from the top of the stadium (which was about 50 feet above the field) and paid more attention to the retractable roof than the game itself, but we still had a ton of fun just hanging out and eating $1 hot dogs and just being in the atmosphere of the game.

|

|

| Ashton (part of a different OEDK internship) posing with the field. | Christina, Kalen, me, Caz, Liz, Kelvin, Alex, and Jeremy having fun at the baseball game. |

Although the baseball game was a ton of fun, it majorly cut into our project time, so we returned to work on Thursday eager to make progress on our project… except we were still missing the foam for our cushions, the last of the metal struts we ordered, and Joe.

So, instead we took our time cleaning off the metal struts, measuring them to make sure they fit together, and determining exactly what welds needed to be made and in what order to ensure that when/if we did get access into the welding lab, we would be as efficient as possible. It was a little difficult trying to measure everything out so precisely, but we did our best to match the CAD drawings as precisely as possible, even if we did lose track of our numbering system three times and switch between using letters, numbers, and double letters.

Testing the struts we cut to make sure the holes lined up. The fact that they do so perfectly is a testament to Liz’s precision skills, Alex’s CAD skills, my measuring skills, and Blessings’ sawing skills.

While we were measuring out the welds we would make, we received news that not only did UPS finally deliver our last exterior strut, but the OEDK staff was able to find someone with a key to the welding lab, so we would be able to actually start welding that afternoon! We had just finished measuring out our plans on the actual metal struts when Jeremy, Fernando, and Danny finished setting up the welding lab, so we carried our pieces all the way over to Ryon Lab so we could begin welding. Or rather, so Jeremy could begin welding while we told him what to do. Because we only had a week and a half left of SEED, Jeremy actually did all the welding for us because it would have taken too long for us to learn how to do it properly ourselves. I was slightly disappointed because I had actually done an hour and a half of researching about welding a couple of weeks ago, but it was definitely for the better that he did it because welding is scary and he was able to complete all 30-something welds we needed in about two hours.

Jeremy welding our prototype together using the MIG welder (see, that research did come in handy! I know what MIG welding is!)

Near the end of the welding session, our design required Jeremy to weld a 5-foot strut onto a base and then weld a support strut onto our main device at a 45-degree angle. Because there was no way he could both support the device and weld it together at the same time, I suited up to hold the pieces together while he welded them together. It was interesting to use a welding mask because they are pitch black except for the light the welder gives off, so all I could see were the metal sparks in front of my face, but the protective equipment I was wearing was strong enough that I couldn’t actually feel any of the heat that the steel I was holding was conducting.

Welding the pieces together got us to a stage where we could actually assemble the basic structure of the device. The progress we made was amazing when you thought about it: That morning, we were missing major parts of our project and had only a couple of cut metal pieces to our name, but by that afternoon, we had built our prototype.

We wheeled our prototype back to the OEDK so we could store it for the evening, but on our way we were stopped by other curious SEED interns. They wanted to look at and interact with the device we had just built, so we used the opportunity to conduct some basic tests. When Kelvin tried to jump on it, we found that our casting stand was a little shaky but it would definitely support someones weight. When we tried to get Jake to use it, we discovered that it could be adjusted by one person, but that person had to take precautions to keep the legs from falling over.

All in all, we built a fairly successful prototype, even if it does still have to be completed and improved. We now know the physical downfalls of our prototype that we couldn’t see on paper, and we will take the next couple of days to determine what to fix and how to fix it before presenting it to our client next week. It will take some work to make our device perfect, but after the amount of progress we made just on Thursday, I’m confident we can complete this device on time.